Lalrp.org:

FUNGURUME, Democratic Republic of Congo — Alain Kasongo, burly and goateed, labored for 4 years driving the heavy vans that hauled away tons of cobalt ore from a gaping gap at one of many greatest mines in Congo. The vibrations from the gear and the jolts of driving over tough floor throughout his 12-hour shifts could possibly be bone-rattling, he mentioned. Lastly, the ache in his backbone grew so insufferable that he wanted surgical procedure.

His older brother, Patchou Kasongo Mutuka, labored the identical job on the identical mine. He suffered the identical harm and required the identical surgical procedure — as did 13 different drivers of excavators and vans on the mine who had been interviewed. They lifted their shirts to disclose surgical scars and unfold out rigorously folded medical data confirming their accounts. They in flip named seven extra colleagues who had suffered the identical destiny, all inside a two-year interval.

“It damage so badly after I went residence, I might lie awake at night time,” mentioned Alain Kasongo, 43, displaying bumps and ridges on his physique from what he mentioned had been three operations.

The stress to supply cobalt is great. It’s a necessary ingredient within the batteries of most electrical automobiles and lots of client electronics. And the Democratic Republic of Congo, or Congo for brief, is the king of cobalt. Final 12 months, it accounted for about three-quarters of worldwide manufacturing, in response to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. This cobalt can come at a excessive human worth.

Seven years in the past, revelations about dire working circumstances in Congo’s casual mining sector vaulted into the world’s headlines after Amnesty Worldwide and the Congolese rights group Afrewatch published a report detailing deaths and accidents among the many numerous youngsters working in small-scale, hand-dug mines, usually in manually carved tunnels that continuously collapsed and buried the younger miners alive.

Since then, world urge for food for Congo’s cobalt has grown sharply, largely pushed by a dramatic improve within the demand for EVs. Almost 90 p.c of the cobalt produced in Congo, residence to half the world’s reserves, goes into batteries, together with these utilized by American, French, German, Japanese and South Korean automakers. Demand for cobalt is projected to extend 20-fold by 2040, in response to the Worldwide Power Company.

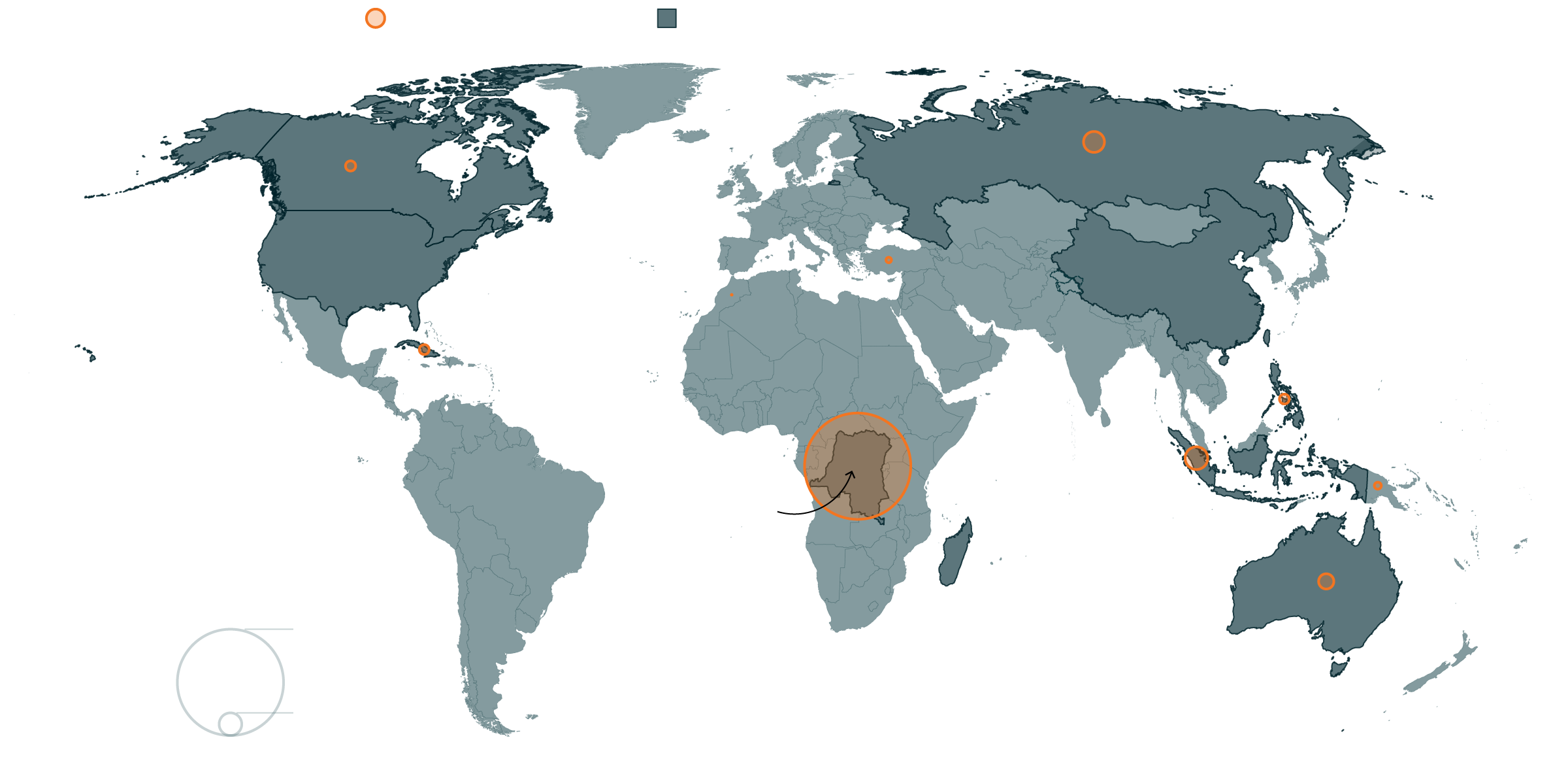

Prime cobalt-

producing nations

International locations with the

largest recognized reserves

Democratic

Republic of Congo

The biggest recognized

cobalt reserves are in

the Democratic Republic

of Congo

The biggest recognized

cobalt reserves are in

the Democratic Republic

of Congo

Prime cobalt- producing nations

International locations with the biggest recognized reserves

Democratic

Republic of Congo

The biggest recognized

cobalt reserves are in

the Democratic Republic

of Congo

The biggest recognized

cobalt reserves are in

the Democratic Republic

of Congo

Prime cobalt-producing nations

International locations with the largest recognized reserves

Democratic

Republic of Congo

The biggest recognized

cobalt reserves are in

the Democratic Republic

of Congo

Prime cobalt-producing nations

International locations with the biggest recognized reserves

Democratic

Republic of Congo

The biggest recognized

cobalt reserves are in

the Democratic Republic

of Congo

Prime cobalt-producing nations

International locations with the biggest recognized reserves

Democratic

Republic of Congo

The biggest recognized

cobalt reserves are in

the Democratic Republic

of Congo

EVs are broadly thought-about essential to addressing local weather change. Their adoption is spreading at a breakneck tempo, fueling hovering demand for minerals together with cobalt, lithium, nickel and manganese that go into constructing EV batteries and the general automobiles. However the extraction and processing of those metals, in far-flung elements of the world, usually take a major and largely unrecognized toll on employees, native communities and the atmosphere.

With out a full accounting, there’s a danger that the green-energy transition might repeat the painful historical past of earlier industrial revolutions.

The Amnesty report about cobalt mining in Congo and the widespread press protection that adopted prompted the industries that produce and use cobalt to set voluntary requirements for the accountable sourcing of the mineral. Many automakers now say they use suppliers which can be audited for adherence to those requirements and that use cobalt solely from mechanized industrial mines, the place little one labor is forbidden.

Clear vehicles, hidden toll

A sequence unearthing the unintended penalties of securing the metals wanted to construct and energy electrical automobiles

These industrial mines accounted for about 89 p.c of Congo’s cobalt manufacturing in 2020, in response to a research by the U.S. Geological Survey, though {industry} insiders mentioned some smaller industrial mines purchase hand-dug ore and embrace it of their tallies. The very greatest mines, operated by firms reminiscent of Swiss-owned Glencore and China Molybdenum (CMOC), say they don’t purchase any ore from hand-dug mines, that are generally known as artisanal mines. Former staff, artisanal mine bosses and residents who dwell close to the mines mentioned in interviews they consider that’s true, noting that it could be onerous to hide truck convoys transferring ore from hand-dug mines.

However unsafe, artisanal mining persists, as does little one labor. In areas visited by Washington Put up journalists, employees in flip-flops and torn T-shirts, together with some who gave the impression to be youngsters, crowded into enormous open pits or descended into the tunnels that honeycomb the bottom. Their ore is often purchased by middlemen and smaller industrial mines, refined regionally after which shipped to China, the place it disappears within the opaque world provide chain.

But even industrial mining may be hazardous. In interviews, 36 present and former staff at 9 of Congo’s industrial cobalt mines described the harmful work executed daily. Some mentioned their employers handled injured employees properly and provided various jobs, however many instructed of employees who suffered life-changing accidents on the job after which had been both fired or noticed their medical payments rejected, in what they contend was a violation of Congolese legislation.

Patrick Kazadi Mumba, a neurologist in the mining city of Lubumbashi, has handled a whole bunch of miners. He mentioned he knew of a minimum of 150 heavy-machine operators — the drivers of huge vans and excavators — who wanted spinal operations up to now decade, virtually all for herniated disks. They accounted for half his sufferers.

“I used to be seeing very younger individuals with spinal issues,” he mentioned, calling the speed of harm “very uncommon.” Many of the injured operators who had been interviewed for this text had been of their 30s and 40s once they underwent surgical procedure.

Mumba mentioned the variety of these injured is more likely to be far larger than these he has seen, since many mine employees search therapy solely when their disks or vertebrae are so broken that they want operations. Some miners conceal their accidents till they change into insufferable to allow them to proceed working. The instances aren’t restricted to the Tenke Fungurume mine, the place Alain Kasongo and his brother labored — owned by CMOC, the world’s second-biggest cobalt producer — however are frequent throughout Congo’s industrial mines, he mentioned.

Heavy-machine operators say they’re uncovered to fixed, sturdy vibrations for lengthy intervals, each day and night time, as they work 12-hour shifts with just one break, six days in a row. Some nations acknowledge such vibrations as a medical danger that have to be managed. The operators are additionally subjected to frequent jolting, they are saying, as they drive their heavy automobiles alongside uneven dust tracks.

Julie Liang, CMOC’s vice chairman for environmental, social and company governance, mentioned the corporate has adopted a number of measures to guard the well being of heavy-machine operators. The situation of their seats is checked to see in the event that they vibrate, and in the event that they do, the operators are to cease their work instantly in order that upkeep groups can look at the seats and substitute them if obligatory, she mentioned. The corporate additionally checks to ensure that roads within the pit are easy in order that the vans don’t jolt or vibrate, and vans are to be loaded initially with delicate materials in order that heavier boulders don’t make the truck jolt, she mentioned.

Through the previous seven years, the corporate’s occupational well being division has reported that 28 heavy-machine operators have undergone again surgical procedure, in response to Liang. The mine at the moment employs 534 operators.

“Guaranteeing accountable mining practices, together with the well being and security of mineworkers, is crucial for the {industry} future,” mentioned Susannah McLaren, head of accountable sourcing and sustainability on the Cobalt Institute, an {industry} physique. She mentioned firms are inspired to comply with ideas and pointers set by the United Nations, the Worldwide Labor Group and the Group for Financial Cooperation and Growth.

However Gregory Mthembu-Salter, an skilled on Congolese mining who based South Africa-based Phuzumoya Consulting, which researches African political economies and pure sources, mentioned worldwide concern about mining circumstances, so targeted on little one labor, has missed threats to the security and rights of employees within the industrial mines.

“How will you base a inexperienced revolution on trashing Congolese atmosphere and exploiting Congolese employees?” he requested.

Life-changing accidents

Congo — chaotic, corrupt and mired in poverty regardless of glittering riches beneath floor — straddles Africa’s cobalt and copper belt. Highways within the southeast of the nation are choked with vans hauling sacks of midnight-blue cobalt hydroxide powder and stacked plates of burnished copper, two key metals for the worldwide transition to cleaner power.

Most main EV producers use cobalt that’s a minimum of partially sourced from the Tenke Fungurume mine, in response to mapping by Brussels-based Useful resource Issues, which research the administration and affect of mining.

Within the city of Fungurume, males in reflective nylon jackets shout greetings throughout the dusty streets throughout shift adjustments. Pickup vans sporting the mine’s orange flags weave via site visitors. Small outlets showcase gleaming spades and pickaxes.

The mine is the city’s lifeblood. However fortunes can rapidly change.

All 15 of the injured heavy-machine operators who had been interviewed mentioned the mine paid for his or her medical care and spinal operations and stored them on full salaries whereas they recuperated, as required by Congolese legislation. All of them acquired physician’s notes, reviewed by The Put up, saying they may return to work in duties that didn’t entail heavy lifting or publicity to intense vibration.

As a substitute, they mentioned, the mine let practically all of them go.

With out work, most misplaced their houses. Some noticed their households break up. Others needed to pull their youngsters out of college.

Alain Kasongo’s employer, CMOC, had promised him completely different duties, he mentioned — a aid as a result of he had a spouse and 12 youngsters to help. However after he had completed recuperating from surgical procedure, he mentioned, he was abruptly instructed he had no extra job. He mentioned he was given $9,000, about six months’ pay, as severance.

Kasongo mentioned that when he might not pay faculty charges, the headmaster reprimanded his youngsters in entrance of an meeting and expelled them. The youngest youngsters ran residence in tears. To assist pay for the oldest two to complete faculty and graduate, his spouse started skipping meals and medicine.

“It’s so painful. I want I might die,” he mentioned, ducking his face inside his neckline to wipe away an indignant tear. “I don’t sleep. I’m the daddy. I ought to present.”

Mwambe bin Nkongolo mentioned he returned to the mine after his surgical procedure, however CMOC wouldn’t give him a unique job, regardless of a medical notice. He mentioned he resumed his outdated duties and labored for 3 months till extreme ache and the concern of crippling himself led him to stop. He left behind a scathing letter of grievance.

Liang mentioned CMOC’s coverage is to present new, appropriate jobs to staff who’ve been injured till they’re in a position to return to their authentic work. If a employee is completely unable to renew their authentic job, the corporate tries to “reallocate the worker in step with his or her present talents,” she mentioned. When that fails, after six months of sick depart, the worker may be legally fired on “grounds of unfitness,” Liang added.

Some have tried to seek out various work in different mines, however they mentioned their scars meant they couldn’t go medical exams to get employed.

“Who will make use of me like this?” requested Christian Mutamba Njenge, who recounted receiving injected painkillers for 2 years earlier than present process spinal surgical procedure and dropping his job. Since then, his spouse has left him, taking their youngsters.

Claims of paltry compensation

Comparable tales about poor therapy had been repeated in interviews with present and former employees who had been injured at industrial mines scattered throughout southeastern Congo. However the nature of the accidents diverse broadly. Many of those staff spoke on the situation of anonymity for concern of retaliation.

One employee, whose fingertip was severed by a machine, mentioned his supervisor dumped him on the entrance of the mine whereas he was nonetheless bleeding, leaving him to discover a taxi to get to the hospital by himself.

One other employee mentioned his wages had been slashed by two-thirds as he recovered after a badly soldered pipe sprayed him within the face with acid.

Yet one more recounted that his household needed to save up cash to have steel pins faraway from his leg after a office harm as a result of the corporate wouldn’t cowl the associated fee.

In one of many mining cities, in a cluster of crumbling homes on an alley choked with flattened plastic bottles and chicks scrambling underfoot, lives a employee who tried to battle for his rights.

Now 30, the person was injured a few years in the past whereas working for a subcontractor at one of many nation’s largest mines. He had been making an attempt to restore a machine, he mentioned, when his supervisor pressed the fallacious button and by accident unloaded a pipeful of cement into his face.

The employee mentioned he suffered everlasting injury to his eyes that required surgical procedure and three months of recuperation. When he went to gather his paycheck, he was fired and instructed that even the wage for the final month he had labored — $150 — was being withheld to assist cowl the prices incurred by the corporate for his medical therapy.

The employee recounted submitting a court docket case, in search of $9,000 in damages. The clerk requested him for $50 to make an organization consultant seem in court docket. He paid however nothing occurred. Then he went to the federal government labor workplace, which requested him for $350 to open a case. He didn’t have it, so he borrowed it. However when his spouse developed breast most cancers, the cash went for her operation as a substitute, he mentioned.

Broke, he couldn’t even afford to purchase method for his 8-month-old daughter, he mentioned. The newborn got here down with a fever and died.

“Her identify was Mirene,” his spouse mentioned softly.

Josué Kashal, a human rights lawyer who runs the Centre d’Aide Juridico-Judiciaire, started bringing employees’ instances in opposition to the economic mining firms in 2019. His workplace is within the boomtown of Kolwezi, the place concrete partitions topped with razor wire bisect the large tawny steppes of mining waste towering over town. Kashal has a submitting cupboard stuffed with instances. Progress is gradual. Lots of his purchasers simply quit.

One among his purchasers is Jean Ngoy Kazadi, a former safety guard on the Pumpi mine, which belongs to Chinese language-majority-owned Lamikal. Kazadi was shot throughout a theft on the mine early final 12 months. One among his legs needed to be amputated.

Eighteen months later, he says, his employer, a subcontractor referred to as Balto, nonetheless received’t pay the medical invoice. So the hospital is detaining him till the invoice is paid — a typical follow in African medical facilities to make sure that debtors don’t abscond. Every day, the invoice will increase $20, and it not too long ago topped $10,000. It’s greater than he ever made on the mine.

Thierry Alamba, who runs Balto, mentioned, “Our lawyer needs to barter with [the hospital]. It is vitally costly for us.” He referred additional inquiries to Balto’s lawyer, who didn’t reply. Lamikal didn’t reply to requests for remark.

Kazadi, 43, a father of six youngsters, is determined. “I’ve obtained no wage, no meals; my children don’t go to highschool,” he mentioned dolefully as he shuffled alongside the tiled ground towards his room. He spends his afternoons sitting simply contained in the hospital’s freshly painted white fence, staring on the sun-drenched, bougainvillea-lined avenue simply out of attain.

Subcontracted employees in danger

Kazadi’s predicament is frequent, in response to docs interviewed in three of Congo’s largest mining cities, particularly amongst employees employed by subcontractors for the mining firms.

The massive firms often pay a stipend to assist cowl well being look after employees and their households, the docs mentioned, although the quantity and high quality of well being care varies from mine to mine. However a 2021 report by Rights and Accountability in Growth (RAID), a London-based company watchdog group targeted on Africa, mentioned that about 57 p.c of employees within the 5 largest mines in Congo are employed by subcontractors. In contrast with these instantly employed by the mining firms, these employees are often paid much less and don’t obtain the identical advantages, the group mentioned.

“Subcontracted employees usually lack the fundamental minimal necessities for well being and security, they usually earn extraordinarily low wages,” mentioned Anaïs Tobalagba, a authorized and coverage researcher for RAID. “Many lack fundamental protecting gear and, when injured, are fired as a result of their employers merely don’t need to pay for medical care or are solely prepared to pay an insignificant quantity.”

To keep away from bringing staff instantly onto their payroll, as required by legislation, mining firms usually change amongst subcontractors when these corporations’ short-term contracts expire.

The staff of some subcontractors mentioned in interviews that they had been usually anticipated to work for months with out a time without work and that their pay can be docked in the event that they took one. One man mentioned he had labored 14 straight months on the Tenke Fungurume mine with out a weekend off.

On this case, Liang mentioned, the subcontractor’s coverage was to present its employees 4 days of paid depart every month.

Requested in regards to the basic therapy and hours of subcontractors’ staff at Tenke Fungurume, Liang mentioned, “The subcontractors have and implement their very own insurance policies and we guarantee, via due diligence and onsite monitoring, that they adjust to the legislation and don’t contradict CMOC insurance policies.” She added: “All staff and contractors are made conscious of the complaints hotline and inspired to report violations. The corporate has applicable procedures in place for investigating and coping with reported violations.”

Underneath Congolese legislation, employers are required to pay for the therapy of employees injured on the job, and staff are entitled to 2 consecutive days off after seven days of labor.

Perilous artisanal mining persists

Within the years after Amnesty’s revelations, the very largest mining firms moved to insulate their ore from that dug by hand within the small-scale mines. These large firms function their very own on-site cobalt refineries to stop any mixing.

However some smaller firms do purchase instantly from the artisanal mines. Or, at native refineries, these firms combine their machine-excavated ore with hand-dug ore from artisanal mines. This cobalt finally finds its approach into the worldwide provide chain.

At a few of the hand-dug mines, employees load the ore onto the again of motorbikes or into vans that haul it to depots run by middlemen, regionally generally known as “negotiateurs.” The biggest of those depots is at Musompo, the place the nicknames of negotiateurs, reminiscent of “Boss Djo” and “Madame Wu,” are scrawled throughout battered sheet-metal indicators in entrance of the stalls.

Different artisanal mines, reminiscent of Shabara, strike direct offers with firms whose vans rumble into the pits and carry off sacks of ore, or with native refineries that course of it for export.

Regardless of the furor over little one labor and treacherous working circumstances, eliminating the artisanal mining sector can be a catastrophe as a result of it helps about 200,000 miners and their households, mentioned Jacques Kaumba Mukumbi, the mining minister for Lualaba province.

Lately, the Congolese authorities, international firms and the industry-funded Honest Cobalt Alliance have sought to work with the cooperatives that run some artisanal mines to enhance their circumstances. However the cash required to reinforce security is scarce.

SAEMAPE, the government-backed union charged with monitoring security within the hand-dug mines and making certain that tunnels don’t exceed 30 meters (slightly below 100 ft) in size, is so poorly funded that staffers usually need to pay bike taxis out of their very own pockets to journey among the many websites, in response to a SAEMAPE consultant who spoke on the situation of anonymity to be candid.

RCS International, an auditing agency partly funded by Western multinational firms, screens six artisanal mining websites, and its suggestions have helped enhance security and cut back little one labor, in response to information offered by the group. However these mines nonetheless recorded 65 deaths between the beginning of 2019 and this Might, the information reveals. Essentially the most sturdy security measures, reminiscent of utilizing equipment to clear away earth that may collapse into tunnels, are costly, mentioned Nicholas Garrett, director of RCS International. So accidents stay frequent.

In June, such a tunnel collapse on the Midingi mine trapped 35-year-old Fiston Ngoy wa Nyembwe. When the earth started to shift, his fellow miners scrambled to the floor, however he was the deepest within the tunnel and couldn’t escape.

For 18 days, he had no gentle or meals, and nobody heard his screams. “I assumed I might die,” he mentioned from a hospital mattress. “I prayed rather a lot. I thought of my household.”

In the end, employees digging for ore close by broke via the wall of his tunnel and had been shocked to find him alive, mendacity on the bottom, too weak to maneuver. He had survived on moisture dripping via the tunnel partitions, a fellow employee mentioned.

He was dragged to the floor — his eyes bandaged in opposition to the unfamiliar gentle — to cheers that echoed across the pits.